SaveSaveSaveSave

Surface Insulation Resistance (SIR) and Flux Designation (ROL) Defined

Phil Zarrow: Eric, the topic of surface insulation resistance, SIR. What exactly is it? What are we doing here?

Eric Bastow: Well, simply put you are measuring the electrical reliability of a no-clean flux residue. Typically, a solder paste, but it could also be wave flux or other types of fluxes as well. It's really important, because we live in a world where the bulk of electronics are commercial. They are not cleaned. The flux residue does stay on the device for the life of the device. The manufacturer, or the end-user of the flux, has to make sure that the flux is not going to conduct, it's not going to leak current, and have electrical signals going where they should not be. Because circuitry is so small, and potentially you have a lot of flux making contact with all these different surfaces, you have to make sure it's not going to conduct.

Phil Zarrow: Just off hand, what is the percentage of the industry, from your perspective, using no-clean now?

Eric Bastow: I would say it's about 80%.

Phil Zarrow: 80%.

Eric Bastow: Or something like that.

Phil Zarrow: Sounds about right. Wow, we've come a long way. That's amazing. With regard to SIR testing, I think a lot of people have seen, and a number of them don't even know what that little SIR comb is or how it works. Can you explain that a little bit?

Eric Bastow: Sure. The most common board that's used, that's prescribed by IPC, is called an IPC-B-24 board. On a single board, there are four patterns—A through D. Basically each pattern is just interlacing traces, and there's a gap in between the traces. What you would do, in the case of solder paste, you would stencil print paste onto those traces. You would reflow the board, just like you would with any other PCB with solder paste on it. Then what happens is, in the space between those traces, that is where the flux is going to pool because the traces themselves are copper, so the solder wets and sticks to the traces, where again the flux pools in between. Then, you can take that board, you can put it in a test chamber, and you can apply a bias, such that trying to see if that residue will conduct.

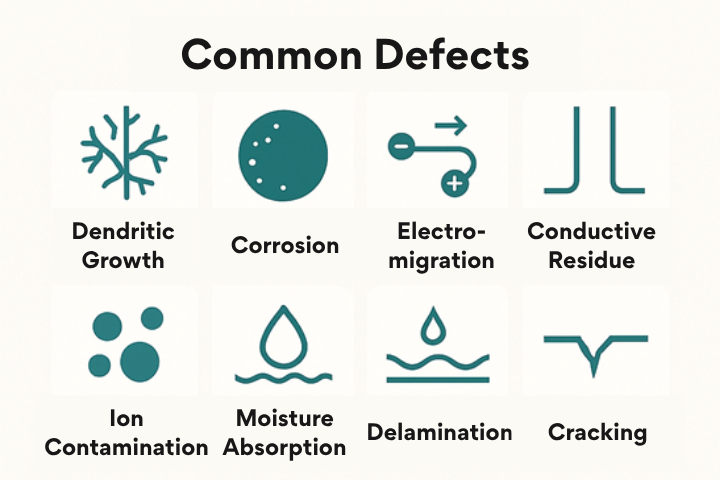

Phil Zarrow: If we can grow dendrites.

Eric Bastow: That's the other thing, too, is the residue corrosive. Then under the influence of bias, can you grow dendrites?

Phil Zarrow: Then of course, you take it out and do measurements to see if indeed… What that resistivity is?

Eric Bastow: You are doing the measurements while the bias is applied.

Phil Zarrow: Same process. Okay, good.

Eric Bastow: It's also done within a warm, humid climate. This is done according to J-Standard-004—is the document that governs how SIR testing is done. The prior version was A: J-Standard-004A. That had the chamber conditions were 85°C, 85% relative humidity. With the release of J-Standard-004B, or revision B, the chamber conditions changed a little bit. Probably due to the influence of commercial products. Products that are operating at 85°C. Now the chamber conditions are 40°C, but still humid, 90% relative humidity, because moisture is part of what makes things move and conduct and that sort of thing. It's still relatively humid in the test chamber.

Phil Zarrow: Now with the actual measurements we're making, we're talking something in the mega Ohm range, correct?

Eric Bastow: That is correct.

Phil Zarrow: How practical is this for the typical practitioner to do this at home so to speak? Or is this something that you would want a lab to perform?

Eric Bastow: I think you would want a lab to perform it. It's very specialized equipment. You're looking at the IPC limit for a "pass" is 1 x 108, or 100 mega Ohms. Very, very high resistance that you're probably not going to be able to do with a volt Ohm meter.

Phil Zarrow: Right. I was going to say how many people have mega Ohm meters kicking around at the shop?

Eric Bastow: Right.

Phil Zarrow: Exactly. Another term that we see a lot, and I think very few people understand what it is and what it means, is ROL. ROL-0, ROL-1. Can you explain that to us?

Eric Bastow: The first two letters, in this case the RO, what you do is you look at the solids content of the flux. Basically, when you have a material that is designated as RO, it's saying that at least half of the solids are rosin. The rest of it can be other things—thixotropic agents, rheological additives, other things of that nature. It's basically saying it's a rosin-based flux. Then the third character is, you have L, M, H, that's basically just a measure of reactivity of the flux, or if you will, how aggressive it is. Then if you have the fourth character, either a 0 or a 1, goes into whether or not it's halogen-free or halogen-containing.

SIR in particular is more of a reflection, or more relayed to that third character, the L, M, or H. Flux residue that passes SIR is almost synonymous with an L. L designation, low activity. There is a strong relationship between the activity of the flux and the SIR performance.

Phil Zarrow: Eric, where can we go to find papers and experiments discussing where SIR has actually been applied?

Eric Bastow: Indium Corporation has written a number of papers on the topic. People can go to our website www.indium.com , or I myself have written a handful papers on SIR, so they can contact me directly. They can send me an email: [email protected].

Phil Zarrow: Eric, thank you very much.

Eric Bastow: You're very welcome.