Ivy University Professor Patty Coleman was at Simon Pearce Restaurant, having a solo lunch and relaxing as she watched the beautiful waterfall at the restaurant. As she enjoyed their signature cheddar cheese soup, she spied Maggie Benson out of the corner of her eye.

“Maggie, come and join me!” She shouted.

“Wow, Professor Patty! It’s been too long,” Maggie exclaimed.

Maggie was the owner and CEO of Benson Electronics. Patty had been a mentor of hers since she graduated from Ivy University about a decade ago.

After they exchanged pleasantries, Maggie asked, “Do you know of any low-cost statistics software? The main stream statistics software tools have skyrocketed in price, and we only use a few of their many features.”

“Which features do you use?” Patty asked.

“Mainly single-variable and two-variable hypothesis tests. Also, one way analysis of variance for six or less samples,” Maggie answered.

Patty thought for a second and then said, “I have a student who is a whiz at Excel® and needs a project. Let me get with him and see if he can write some Excel® spreadsheets that can do what you need.”

Later that day, Patty’s student, Wen Cao, contacted Maggie’s team and discussed a current statistical analysis problem the team was having. Many of the engineers were new and unfamiliar with statistical analysis.

Mary Chambers, the leader of the team, shared their current challenge.

“We currently have voiding under bottom terminated components at 16.2%. At a brainstorming session, we concluded that if we could find a solder paste that provided 5% less voiding, we would switch to using that solder paste. We tested a new paste and it delivered 9.87% voiding, so we were going to recommend switching. However, Dawn Reynolds, one of the team members, asked if the 9.87% number was statistically significant, and no one knew the answer.” Mary summed up.

Wen responded, “Dawn is correct. Since it is more than 6% less (i.e. 16.2% – 9.87% > 6%), it is tempting to say you met your goal, but you can’t be confident your results are statistically significant. Why don’t you send me your data, and I will make an Excel® spreadsheet that will perform the calculations to determine if the results are statistically significant. I should be able to get back to you in a few days if you send the data today.”

A short time later, Wen sent an email requesting a meeting in two days.

Time seemed to drag as Mary, Dawn and the entire team anticipated Wen’s finding.

Two days later, Wen arrived and Dawn greeted him. “你好 (Nǐ hǎo.)” For a moment, Wen was stunned, no longer used to hearing Chinese greetings at meetings in the United States, but he chuckled and quickly regained his composure. He and Dawn shared a few more words in Chinese, and then decided they should switch to English.

“Wow! Your Chinese is perfect, where did you learn it?” Wen asked.

“My dad was given a 3-year assignment in Beijing when I was 4. My parents sent me to a Chinese speaking school,” Dawn replied.

After a few more pleasantries, they got to the matter at hand.

“An hypothesis test is a useful way to determine if some metric meets a requirement,” Wen began.

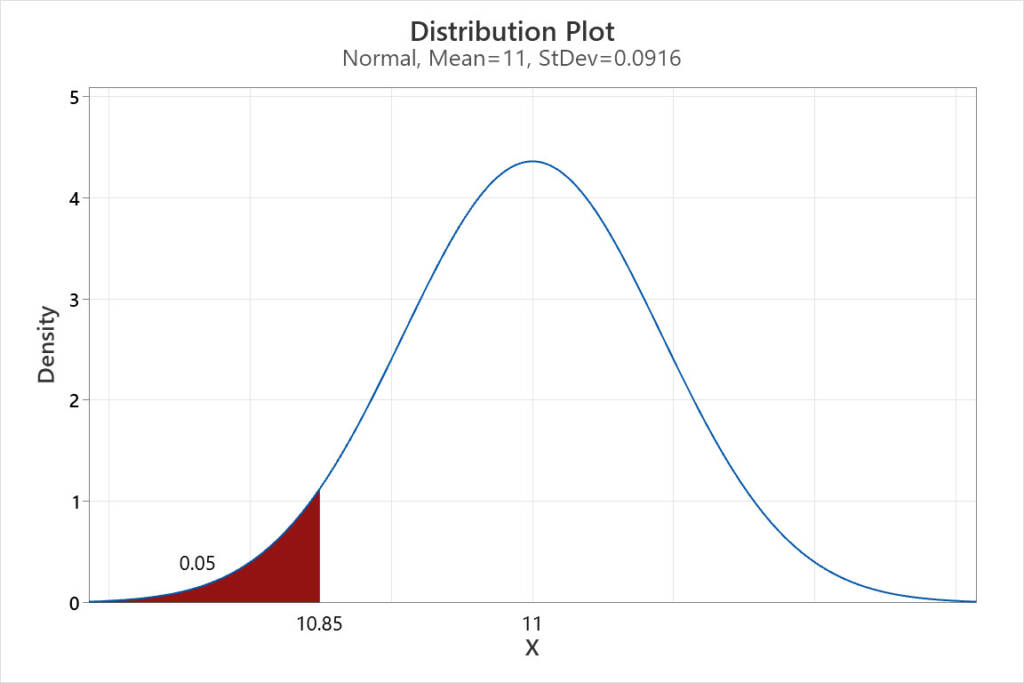

“Let’s consider your problem. You want the mean to be less than 11 and your result was 9.867. The result is less than 11, but is it less with statistical confidence? Consider Figure 1. This is a plot of a sampling distribution of the mean, with an average of 11. Let’s assume the data is normally distributed. The width of the distribution is the standard error of the mean.”

Figure 1. A plot of the sampling distribution of the mean, with an average of 11.

Wen continued. “Note that at 10.85 to the left, on the x axis, the area under the curve is shaded in. This shaded area is only 5% of the total area under the curve. The interpretation is that the likelihood of the true mean being lesser than 10.85 is 5%. Since the value from the data is 9.87, we can say with almost complete certainty that the true mean is less than 11.”

“This analysis is very helpful, but what calculations support it?” Brad Fullagher asked.

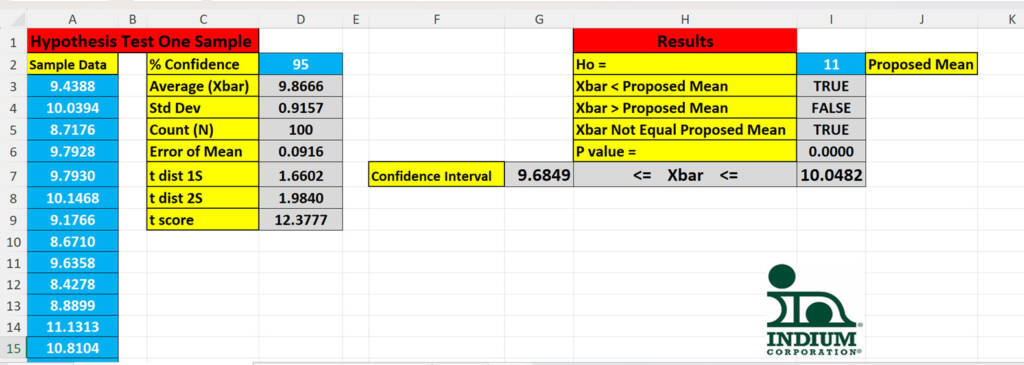

“Thank you for leading us into the next part of my presentation!” Wen chuckled. “I developed an Excel® spreadsheet to perform the calculations.” See Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Excel® calculations supporting the analysis of the voiding data.

“The user enters the data in the column on the left, cells A3:A102. They also specify the percent confidence desired, 95%, in this case, in cell D3, and the proposed mean of 11 in cell I2. Note that data entry cells are blue with white numbers.

“The result is that the average of the data (xbar) is less than the proposed mean is in cell I3. The p value (cell I6) is the likelihood that you would be wrong if you said the mean is less than 11. In this case, there is essentially 0% chance that the mean is not less than 11. The cells that are grey with black letters are calculations.

“Are there any questions?” Wen summed up.

There was a moment of silence and then the 6 members of the team burst into applause. Wen turned red and was speechless.

Matt summed it up, “Most statistics software is so intimidating to use! But what you created is so simple.”

Epilogue: Later that week, a friend noticed a couple that looked suspiciously like Wen and Dawn having dinner at Simon Pearce.

Cheers,

Dr. Ron